Language learners

Some BHS students are taking their passion for language outside of the classroom.

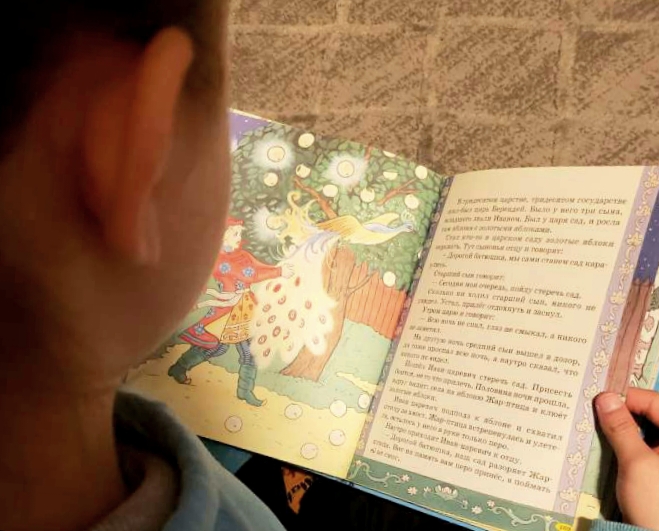

Improving fluency. BHS Junior Elsie Marchuk reads a children’s book in Ukrainian, her parents’ first language. A couple of years ago, Marchuk renewed her attempt to learn the language using books and Duolingo, an app that is used by many BHS students who are learning a language not offered through the school system. “I have been exposed to Ukrainian all my life but still have so much to learn,” Marchuk said.

April 10, 2020

Norwegian, Korean, Swedish and Ukrainian – what do these languages have in common? Despite not being offered through the school language program, a few BHS students are choosing to dedicate some of their free time to learning these languages.

Though their motivations and methods of learning differ, each recognizes the difficulties and benefits of learning another language.

“The world is very connected now, and by being able to learn new languages, a person would be able to more easily navigate and have more opportunities in our world,” BHS junior Elsie Marchuk said.

Some of these students are learning a language because it is part of their heritage. Scandinavian ancestry was a significant factor when BHS senior Jacob Livingston decided to start learning both Swedish and German. He hopes to one day travel to the countries that speak these languages and potentially make one of them home.

“Eventually, I do want to travel a lot, and it helps to know how to speak the languages at least rudimentarily,” Livingston said.

In a similar way, BHS junior Jenna Smith was encouraged to learn Norwegian because her great grandparents spoke the language fluently.

“My ancestors are from Norway, and I have quite a few old books in Norwegian,” Smith said.

Marchuk’s parents are Ukrainian immigrants, so her motivation to learn the language lies in a desire to better understand her family.

“It is hard to learn a new language, and my motivation has been lacking recently, but by learning Ukrainian, I’ll be able to better communicate and grow relationships more with my family members,” Marchuk said.

However, not all of these students have ancestral or familial connections to the language they are learning. BHS junior Callie Wright started practicing Korean about five months ago because she aspires to teach English in South Korea. Korean uses its own alphabet and has a sentence format that differs greatly from English, placing it high in the Foreign Language Institute’s ranking of most difficult languages to learn for English speakers.

“Korean grammar can be quite difficult to get a hold of because it is different from English,” Wright said. “Another difficulty is different types of sentence markers that mark subject, object, location or possession.”

Korean may be especially difficult, but learning any language is not a passive process. It can take significant discipline to start and even more to become fluent, but hard work – as with almost any aspect of life – leads to rewards. A limited number of languages are offered through the school system, but a countless number more can be learned through other resources if one dedicates enough time and effort to the endeavor.

“Our language department seems to be lacking funding due to the low number of kids. If you’re learning a language outside of school, you have multiple options that you can choose from based on your income and lifestyle,” Wright said. “It’s just a matter of setting aside time.”

Each student uses a different combination of resources, but they all admitted to using an app known as Duolingo. Duolingo offers 35 languages and is free, though there are a few additional features that are only offered with a paid subscription. The app is widely considered convenient and versatile, which contributes to its popularity.

“If you’ve [tried] learning languages outside of school, you’ve used Duolingo,” Livingston said.

In addition to Duolingo, Livingston uses a paid app called Babble, reads Swedish news and books and participates in a couple of online groups formed by both learners and native speakers. These resources offer insight into the language as well as the culture, which may be as critical for interaction with native speakers as the language itself.

“The online group is awesome because if there’s a question you have, you just pop in and ask, and someone will get back to you in probably a couple minutes,” Livingston said.

Since she aims to live and teach in South Korea, Wright recognizes the importance of studying Korean culture. According to Wright, Duolingo’s Korean program does not prompt her to speak or write the language, so she uses grammar books to supplement her learning. She also supplements her study of Korean culture by more entertaining means.

“I try to include watching Korean shows or listening to Korean songs because often, learning programs teach formal sentences or stiff sentences,” Wright said.

In Marchuk’s case, studying culture is not necessary. She has, in a way, been studying the Ukrainian language and culture her entire life, but she stresses that she still has much to learn.

“Having immigrant parents, I’ve been exposed to the culture and language all my life,” Marchuk said. “Even though I may have been born in America, that culture is still part of me and valuable.”

Some criticize America for not appreciating other cultures, citing how the country does not – on a federal level – require students to study another language as part of their education. Almost one-third of the globe studies English as a non-native language, and all but two European countries require their students to learn one or more foreign languages in school for at least one year.

“One to two years [of language education] should be mandatory because, if you look at it, everywhere else in the world – except England and Ireland – are almost all bilingual,” Livingston said.

However, there are downsides to requiring all U.S. students to learn another language through the education system. A lack of funding – and a lack of interest – are common concerns.

“Drawbacks, however, could be making students hate language learning if they aren’t interested in the language or don’t care for learning another language,” Smith said.

In most U.S. schools, including BHS, language classes are optional. Some years, a lack of students has forced BHS to combine different levels of a language class – or even cancel that class altogether. With the current level of funding and interest in language education, BHS is only able to offer Spanish, German, French and Latin, but greater interest might yield more opportunities.

“If more people were interested, then yes, we could probably do more language choices,” Livingston said.

If the language a student wants to learn is not offered through their school, countless options do exist on the web, in bookstores and in the app store. For less popular languages, however, resources may be limited.

“I think the accessibility of learning a language really depends on what the language is,” Livingston said.

Regardless, learning a language is never impossible with enough determination and commitment.

“You just need the drive to be able to learn something new,” Marchuk said.